Reason counters, ‘while memory is upfront about its transformations, no documentation fails radically to transform its subject, but often neglects to acknowledge the importance of such mutations’ (Reason, Archive or Memory, 87). If memory is recovered and necessarily altered through the act of remembrance and recollection and as such fleeting, then, so too is the archive’s continual re-collection of a past moment a process of alteration. For Reason, the project is not to expose to shortcomings of the archive, or archive theory, as much as it is to question if we can come to understand the archive as capable of incorporating both the transformations made to the performance act by the archive as well as memory. The archives of detritus that Reason envisions seeks the remains, the fragments and partialities of a performance as a means by which to handle the disappearing state of live performance and memory; the archive of detritus abandons any claim to accuracy, completeness or stability. It seems crucial, however, to ask how might we use Reason’s conceptualization of the archive of detritus as a methodology, as a practice? Is the goal here seeking out silences, seething absences and instability or working within them? What I wish to stress here is that accuracy is simply not worthy but rather unattainable, that even in the process of witnessing liveness, of perception is an act of interpretation and translation. The temporal and spatial distance between the live act and the archival document is not the source of gaps in understanding and perception, for even at the moment of transmission my observation could not have fully approximated the event. Performance, whether mediated or live, is not easily translated.

It is this very untranslatability that characterizes performance, for Diana Taylor. Given this condition of untranslatability, the archive is illuded by live performance. Moreover, liveness–whether performance or embodied memory–cannot be captured by the archive and while, for Taylor, the archive is far from unchanging, there is an implicit apprehension that documentation might replace the performance. It is crucial, perhaps, to think of this replacement not as a replica, or replication, of the performed act but as a stand-in for the live act. While this may be altogether too obvious, performance is always already a reiteration, always in a process of replication. However, in a metonymic fashion the stand-in turns the multiplicity of the existence of the live event and the documentation of such into the singularity of the only. It is from here that Phelan’s dissatisfaction with reproduction resonates most clearly, for me.

Phelan notes that culture reproduces itself by forcing, ‘difference into the Same,’ by forcing the two of gender (masculine and feminine) into the one of the ‘hommo-sexual’ which consequently requires the disappearance of the woman (Phelan, Unmarked, 151). This is not to say that women do not exist but, rather, that they do under the sign of erasure. Simply put, the overvaluation of the masculine, the phallus, produces not an (original) masculine and (poor imitation) feminine but purely the masculine. What is at stake here is the disvaluation of the fleeting, the non-reproductive and the seemingly expendable.

A second application of Phelan’s essay points us in the direction of knowledge production and the role of evidence. I take serious the question of how we know what we, indeed, know. This is not a project of self-flagellation or self-doubt but, rather, a call to take notice of what counts as evidence and the process by which something becomes verifiable. Of interest as well is the contact between the performance (object of analysis) and the role of interlocutor. For Phelan this interaction is, ‘essentially performative’ and therefore resistant to the claims of validity and accuracy endemic to the discourse of reproduction’ (147). For me, this positions Phelan’s initial imperative that, ‘performance’s only life is in the present,’ as concerning not only the inevitable discontinuities between the live event and the writing (or documentation) of it but, more so, an indication that those documents we produce are radically not of the performance (146). What might it effect to think of writing not as a mnemonic memory aid or a replication of memory but as an interrelated, yet, altogether dissimilar enterprise? Ippolito’s variable medium task force questionnaire, in theory, illuminates what the practical application of such questioning might look like.

The challenge in itself, perhaps, is to recognize that performance is irreducible to text and yet is a necessary and productive object of analysis. The appeal of being trained in performance studies, as opposed to other fields, is the opportunity to bring the ‘repertoire’ into contact with the archive, to ignore neither the live, the document nor memory. For Taylor, this is the act of turning one’s attention to ‘scenarios.’ While her critical call is to value the repertoire, the methodology implied is not as simple as a turn to the live. Her project is not to translate these points of contact into the other (i.e. the embodied into document and the document into the live) but, more so, to harvest each.

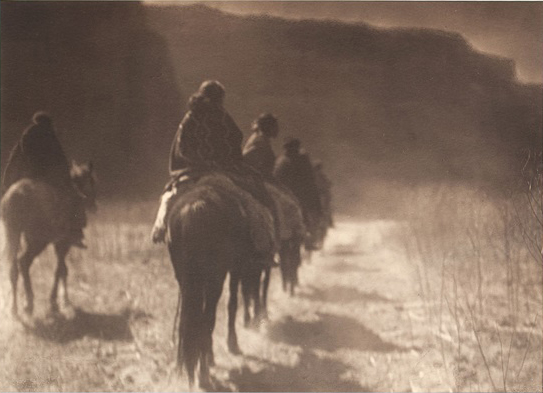

I have raised the question, by way of the title, how do we do things with disappearance? And while it is a cheap reference to Austin’s How to do Things with Words, these readings stir a sound need to consider precisely how to attend to disappearance. This, now altogether too long response, is not the place to do just that however. Rather, I return Curtis’ 1904 photograph The Vanishing Race. Curtis desperately wanted to preserve Indian tradition and culture and, yet, his work amounts to not the preservation but the authentication of the culture. When we ask the question of how preservation, driven by a colonial nostalgia, demands this performance of authenticity we collide with what Taylor refers to as preservation as a form of erasure. Still yet, erasure and even disappearance need not denote a void or blankness as there is still a trace, an indelible mark to heed.