Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance. To the degree that performance attempts to enter the economy of reproduction it betrays and lessens the promise of its own ontology. Performance’s being, like the ontology of subjectivity proposed here, becomes itself through disappearance.

The pressures brought to bear on performance to succumb to the laws of the reproductive economy are enormous. For only rarely in this culture is the “now” to which performance addresses its deepest questions valued. (This is why the now is supplemented and buttressed by the documenting camera, the video archive.) Performance occurs over a time which will not be repeated. It can be performed again, but this repetition itself marks it as “different.” The document of a performance then is only a spur to memory, an encouragement of memory to become present.

The other arts, especially painting and photography, are drawn increasingly toward performance. The French-born artist Sophie Calle, for example, has photographed the galleries of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Several valuable paintings were stolen from the museum in 1990. Calle interviewed various visitors and members of the museum staff, asking them to describe the stolen paintings. She then transcribed these texts and placed them next to the photographs of the galleries. Her work suggests that the descriptions and memories of the paintings constitute their continuing “presence,” despite the absence of the paintings themselves. Calle gestures toward a notion of the interactive exchange between the art object and the viewer. While such exchanges are often recorded as the stated goals of museums and galleries, the institutional effect of the gallery often seems to put the masterpiece under house arrest, controlling all conflicting and unprofessional commentary about it. The speech act of memory and description (Austin’s constative utterance) becomes a performative expression when Calle places these commentaries within the representation of the museum. The descriptions fill in, and thus supplement (add to, defer, and displace) the stolen paintings. The fact that these descriptions vary considerably—even at times wildly—only lends credence to the fact that the interaction between the art object and the spectator is, essentially, performative—and therefore resistant to the claims of validity and accuracy endemic to the discourse of reproduction. While the art historian of painting must ask if the reproduction is accurate and clear, Calle asks where seeing and memory forget the object itself and enter the subject’s own set of personal meanings and associations. Further her work suggests that the forgetting (or stealing) of the object is a fundamental energy of its descriptive recovering. The description itself does not reproduce the object, it rather helps us to restage and restate the effort to remember what is lost. The descriptions remind us how loss acquires meaning and generates recovery—not only of and for the object, but for the one who remembers. The disappearance of the object is fundamental to performance; it rehearses and repeats the disappearance of the subject who longs always to be remembered.

For her contribution to the Dislocations show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1991, Calle used the same idea but this time she asked curators, guards, and restorers to describe paintings that were on loan from the permanent collection. She also asked them to draw small pictures of their memories of the paintings. She then arranged the texts and pictures according to the exact dimensions of the circulating paintings and placed them on the wall where the actual paintings usually hang. Calle calls her piece Ghosts, and as the visitor discovers Calle’s work spread throughout the museum, it is as if Calle’s own eye is following and tracking the viewer as she makes her way through the museum.1This notion of following and tracking was a fundamental aspect of Calle’searlier performance pieces. See Jean Baudrillard Suite Venitienne/Sophie Calle, Please Follow Me, for documentation of Calle’s surveillance of a stranger. Moreover, Calle’s work seems to disappear because it is dispersed throughout the “permanent collection”—a collection which circulates despite its “permanence.” Calle’s artistic contribution is a kind of self-concealment in which she offers the words of others about other works of art under her own artistic signature. By making visible her attempt to offer what she does not have, what cannot be seen, Calle subverts the goal of museum display. She exposes what the museum does not have and cannot offer and uses that absence to generate her own work. By placing memories in the place of paintings, Calle asks that the ghosts of memory be seen as equivalent to “the permanent collection” of “great works.” One senses that if she asked the same people over and over about the same paintings, each time they would describe a slightly different painting. In this sense, Calle demonstrates the performative quality of all seeing.

IPerformance in a strict ontological sense is nonreproductive. It is this quality which makes performance the runt of the litter of contemporary art. Performance clogs the smooth machinery of reproductive representation necessary to the circulation of capital. Perhaps nowhere was the affinity between the ideology of capitalism and art made more manifest than in the debates about the funding policies for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA)2See my essays “Money Talks” and “Money Talks, Again” for a full elaboration.. Targeting both photography and performance art, conservative politicians sought to prevent endorsing the “real” bodies implicated and made visible by these art forms.

To attempt to write about the undocumentable event of performance is to invoke the rules of the written document and thereby alter the event itself. Just as quantum physics discovered that macro-instruments cannot measure microscopic particles without transforming those particles, so too must performance critics realize that the labor to write about performance (and thus to “preserve” it) is also a labor that fundamentally alters the event. It does no good, however, to simply refuse to write about performance because of this inescapable transformation. The challenge raised by the ontological claims of performance for writing is to re-mark again the performative possibilities of writing itself. The act of writing toward disappearance, rather than the act of writing toward preservation, must remember that the after-effect of disappearance is the experience of subjectivity itself.

The distinction between performative and constative utterances was proposed by J.L.Austin in How To Do Things With Words.5J.L.Austin, How To Do Things With Words, 2nd edn. Derrida’s rereading of Austin also comes from an interest in the performative element withinlanguage. Austin argued that speech had both a constative element (describing things in the world) and a performative element (to say something is to do or make something, e.g. “I promise,” “I bet,” “I beg”). Performative speech acts refer only to themselves, they enact the activity the speech signifies. For Derrida, performative writing promises fidelity only to the utterance of the promise: I promise to utter this promise.6Jacques Derrida, “Signature, Event, Context.” The performative is important to Derrida precisely because it displays language’s independence from the referent outside of itself. Thus, for Derrida the performative enacts the now of writing in the present time.7See Felman, The Literary Speech Act, for a dazzling reading of Austin.

Tania Modleski has rehearsed Derrida’s relation to Austin and argues that “feminist critical writing is simultaneously performative and utopian” (“Some Functions”: 15). That is, feminist critical writing is an enactment of belief in a better future; the act of writing brings that future closer.8See my essay, “Reciting the Citation of Others” for a full discussion of Modleski’s essay and performance. Modleski goes further too and says that women’s relation to the performative mode of writing and speech is especially intense because women are not assured the luxury of making linguistic promises within phallogocentrism, since all too often she is what is promised. Commenting on Shoshana Felman’s account of the “scandal of the speaking body,” a scandal Felman elucidates through a reading of Molière’s Dom Juan, Modleski argues that the scandal has different affects and effects for women than for men. “[T]he real, historical scandal to which feminism addresses itself is surely not to be equated with the writer at the center of discourse, but the woman who remains outside of it, not with the ‘speaking body,’ but with the ‘mute body’” (ibid.: 19). Feminist critical writing, Modleski argues, “works toward a time when the traditionally mute body, ‘the mother,’ will be given the same access to ‘the names’—language and speech—that men have enjoyed” (ibid.: 15).

If Modleski is accurate in suggesting that the opposition for feminists who write is between the “speaking bodies” of men and the “mute bodies” of women, for performance the opposition is between “the body in pleasure” and, to invoke the title of Elaine Scarry’s book, “the body in pain.” In moving from the grammar of words to the grammar of the body, one moves from the realm of metaphor to the realm of metonymy. For performance art itself however, the referent is always the agonizingly relevant body of the performer. Metaphor works to secure a vertical hierarchy of value and is reproductive; it works by erasing dissimilarity and negating difference; it turns two into one. Metonymy is additive and associative; it works to secure a horizontal axis of contiguity and displacement. “The kettle is boiling” is a sentence which assumes that water is contiguous with the kettle. The point is not that the kettle is like water (as in the metaphorical love is like a rose), but rather the kettle is boiling because the water inside the kettle is. In performance, the body is metonymic of self, of character, of voice, of “presence.” But in the plenitude of its apparent visibility and availability, the performer actually disappears and represents something else—dance, movement, sound, character, “art.” As we discovered in relation to Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits, the very effort to make the female body appear involves the addition of something other than “the body.” That “addition” becomes the object of the spectator’s gaze, in much the way the supplement functions to secure and displace the fixed meaning of the (floating) signifier. Just as her body remains unseen as “in itself it really is,” so too does the sign fail to reproduce the referent. Performance uses the performer’s body to pose a question about the inability to secure the relation between subjectivity and the body per se; performance uses the body to frame the lack of Being promised by and through the body— that which cannot appear without a supplement.

As MacCannell points out about Lacan’s story of the “laws of urinary segregation” (Ecrits: 151), same sex bathrooms are social institutions which further the metaphorical work of hiding gender/genital difference. The genitals themselves are forever hidden within metaphor, and metaphor, as a “cultural worker,” continually converts difference into the Same. The joined task of metaphor and culture is to reproduce itself; it accomplishes this by turning two (or more) into one.9Juliet MacCannell, Figuring Lacan: Criticism and the Cultural Unconscious, esp. pp. 90–117. By valuing one gender and marking it (with the phallus) culture reproduces one sex and one gender, the hommo-sexual.

If this is true then women should simply disappear—but they don’t. Or do they? If women are not reproduced within metaphor or culture, how do they survive? If it is a question of survival, why would white women (apparently visible cultural workers) participate in the reproduction of their own negation? What aspects of the bodies and languages of women remain outside metaphor and inside the historical real? Or to put it somewhat differently, how do women reproduce and represent themselves within the figures and metaphors of hommo-sexual representation and culture? Are they perhaps surviving in another (auto)reproductive system?

“What founds our gender economy (division of the sexes and their mutual evaluation) is the exclusion of the mother, more specifically her body, more precisely yet, her genitals. These cannot, must not be seen” (original emphasis; MacCannell, Figuring Lacan: 106). The discursive and iconic “nothingness” of the Mother’s genitals is what culture and metaphor cannot face. They must be effaced in order to allow the phallus to operate as that which always marks, values, and wounds. Castration is a response to this blindness to the mother’s genitals. In “The Uncanny” Freud suggests that the fear of blindness is a displacement of the deeper fear of castration but surely it works the other way as well, or maybe even more strongly. Averting the eyes from the “nothing” of the mother’s genitals is the blindness which fuels castration. This is the blindness of Oedipus. Is blindness necessary to the anti-Oedipus? To Electra? Does metonymy need blindness as keenly as metaphor does?

Cultural orders rely on the renunciation of conscious desire and pleasure and promise a reward for this renunciation. MacCannell refers to this as “the positive promise of castration” and locates it in the idea of “value” itself—the desire to be valued by the Other. (For Lacan, value is recognition by the Other.) The hope of becoming valued prompts the subject to make sacrifices, and especially to forgo conscious pleasure. This willingness to renounce pleasure implies that the Symbolic Order is moral and that the subject obeys an (inner) Law which affords the subject a veil of dignity. Why only the veil of dignity as against dignity itself? Because the fundamental Other (the one who governs “the other scene” which ghosts the conscious scene) is the Symbolic Mother. She is the Ideal Other for whom the subject wants to be dignified; but she cannot appear within the phallic representational economy which is predicated on the disappearance of her Being.10The disappearance of the Mother’s Being also accounts for the (relative)success of the visibility of the anti-abortion groups. The smooth displacementof the image of the Mother to the hyper-visible image of the hitherto unseenfetus, is accomplished precisely because the Being of the Mother is what isalways already excluded within representational economies. See Chapter 6 in this volume for further elaboration of this point. The psychic subject performs for a phantom who allows the subject veils and curtains— rather than satisfaction.

Performance approaches the Real through resisting the metaphorical reduction of the two into the one. But in moving from the aims of metaphor, reproduction, and pleasure to those of metonymy, displacement, and pain, performance marks the body itself as loss. Performance is the attempt to value that which is nonreproductive, nonmetaphorical. This is enacted through the staging of the drama of misrecognition (twins, actors within characters enacting other characters, doubles, crimes, secrets, etc.) which sometimes produces the recognition of the desire to be seen by (and within) the other. Thus for the spectator the performance spectacle is itself a projection of the scenario in which her own desire takes place.

More specifically, a genre of performance art called “hardship art” or “ordeal art” attempts to invoke a distinction between presence and representation by using the singular body as a metonymy for the apparently nonreciprocal experience of pain. This performance calls witnesses to the singularity of the individual’s death and asks the spectator to do the impossible—to share that death by rehearsing for it. (It is for this reason that performance shares a fundamental bond with ritual. The Catholic Mass, for example, is the ritualized performative promise to remember and to rehearse for the Other’s death.) The promise evoked by this performance then is to learn to value what is lost, to learn not the meaning but the value of what cannot be reproduced or seen (again). It begins with the knowledge of its own failure, that it cannot be achieved.

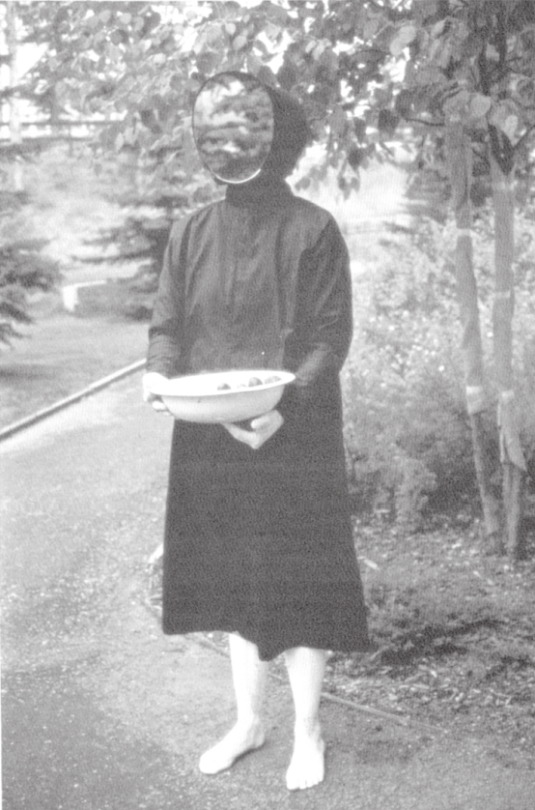

IIAngelika Festa creates performance pieces in which she appears in order to disappear (Figure 24). Her appearance is always extraordinary: she suspends herself from poles; she sits fully dressed in well-excavated graves attended by a fish; she stands still on a crowded corner of downtown New York (8th and Broadway) in a red rabbit suit holding two loaves of bread; wearing a mirror mask, a black, vaguely antiquarian dress, with hands and feet painted white, she holds a white bowl of fruit and stands on the side of a country road. The more dramatic the appearance, the more disturbing the disappearance. As performances which are contingent upon disappearance, Festa’s work traces the passing of the woman’s body from visibility to invisibility, and back again. What becomes apparent in these performances is the labor and pain of this endless and liminal passing.

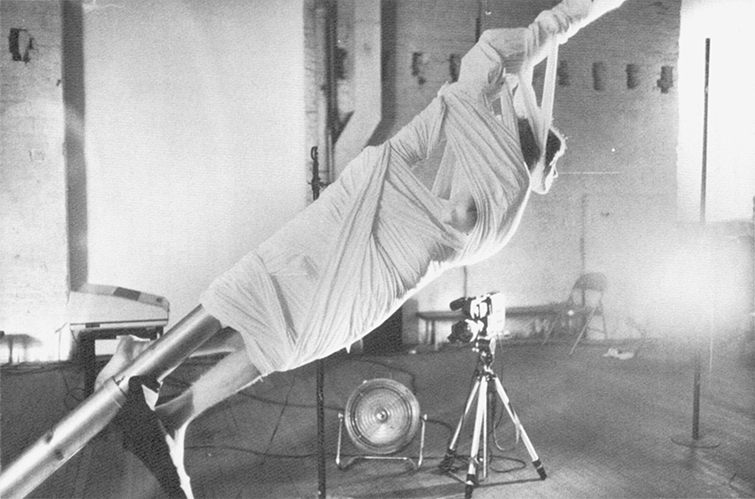

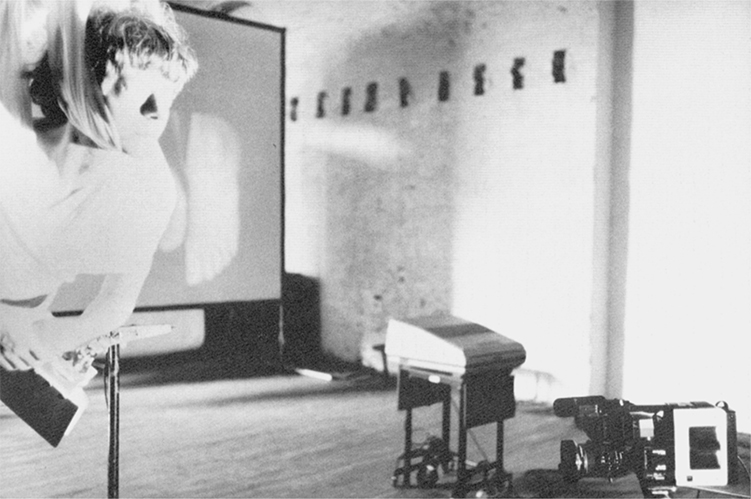

In her 1987 performance called—appropriately—Untitled Dance (with fish and others), at The Experimental Intermedia Foundation in New York, Festa literally hung suspended from a pole for twenty-four hours (Figure 25).11Some of the description of this performance first appeared in my essay “Feminist Theory, Poststructuralism, and Performance.” The performance took place between noon on Saturday May 30 and noon on Sunday 31. The pole was positioned between two wooden supports at about an 80° angle and Festa hung suspended from it, her body wrapped to the pole with white sheets, her face and weight leaning toward the floor. Her eyes were covered with silver tape and thus looked, in all senses, beyond the spectator. About two and a half feet from the bottom of the pole was a small black cushion which supported her bare feet. Her feet in turn were projected onto a screen behind her to the left in close-up. The projection enlarged them so much that they seemed to be as large as the rest of Festa’s body. On a video monitor in front of Festa and to the left, a video tape loop of the embryology of a fish played continuously. Finally, on a smaller monitor facing Festa a time-elapsed video documenting the dance (re)played and re(in)flected the entire performance.

The images of death, birth, and resurrection are visually overlaid; Festa’s point is that they are philosophically (and mythologically) inseparable. The work is primarily a spectacle of pain; while I do not wish to minimize this aspect of the performance, I will begin by discussing some of the broad claims which frame Untitled. The performance seeks to display the lack of difference between some of Western metaphysics’ tacit oppositions—birth and death, time and space, spectacle and secret. By suspending herself between two poles (two polarities), Festa’s performances suggest that it is only within the space between oppositions that “a woman” can be represented. Such representation is, therefore and necessarily, extremely up-in-the-air, almost impossible to map or lay claim to. It is in a space in which there is no ground, a space in which (bare)feet cannot touch the ground.

The iconography of the performance is self-contradictory: each position is undermined by a succeeding one. Festa’s wrapped body itself seems to evoke images of dead mummies and full cocoons. Reading the image one can say something like: the fecundity of the central image is an image of History-as-Death (the mummy) and Future-as-Unborn (the cocoon). The twenty-four-hour performance defines the Present (Festa’s body) as that which continually suspends and thus prohibits the intrusive return of that death and the appealing possibility of that birth. The Present is that which can tolerate neither death nor birth but can only exist because of these two “originary” acts. Both are required for the Present to be present, for it to exist in the suspended animation between the Past and the Future.

But this truism is undercut by another part of the performance: the fish tape stops at precisely the moment the fish breaks out of the embryo; then the tape begins again. The tape thus revises the definition of History offered by the central image (History-as-Death). History is figured by the tape as an endless embryology whose import is not in the breaking out of—(the ubiquitous claim to historical “transformation”)—but rather in the continual repetition of the cycle of that mutation which produces birth. (“Be fruitful and multiply” is wittily made literal by the repeated projection of the tape loop.)

The third image then undercuts the first two. The projected images of Festa’s feet seem to be an half-ironic, half-devout allusion to the history of representations of the bloody feet of the crucified Christ (Figure 26). On the one hand, (one foot?) the projections are like photographic “details” of Mannerist paintings and on the other, they seem to “ground” the performance; because of their size they demand more of the spectator’s attention. The spatial arrangement of the room—with Festa in the middle, the feet-screen behind her and to the left, the fish tape in front of her also on the left, and the time-elapsed mini-monitor directly in front of her and raised, forces the spectator constantly to look away from Festa’s suspended body. In order to look at the projected feet, one has to look “beyond” Festa; in order to look at the fish embryo tape or the video monitor recording the performance itself, one has to turn one’s back to her. That these projected images seem to be consumable while the center image is, as it were, a “blind” image, suggests that it is only through the second-order of re/ presentation that we “see” anything. Festa’s body (and particularly her eyes) is averted from the spectator’s ability to comprehend, to see and thus to seize.

The failure to see the eye/I locates Festa’s suspended body for the spectator. The spectator’s inability to meet the eye defines the other’s body as lost; the pain of this loss is underlined by the corollary recognition that the represented body is so manifestly and painfully there, for both Festa and the spectator. Festa cannot see her body because her eyes are taped shut; the spectator cannot see Festa and must gaze instead at the wrapped shell of a lost eyeless body. As with Wallace Stevens: “The body is no body to be seen/But is an eye that studies its black lid”—and its back lid—the Nietzschean hinterfrage (Stevens, “Stars at Tallapoosa”).

[...]

Sight is both an image and a word; the gaze is possible both because of the enunciations of articulate eyes and because the subject finds a position to see within the optics and grammar of language. In denying this position to the spectator Festa and Simpson also stop the usual enunciative claims of the critic. While the gaze fosters what Lacan calls “the belong to me aspect so reminiscent of property” (Four Fundamental Concepts: 81) and leads the looker to desire mastery of the image, the pain inscribed in Festa’s performance makes the viewer feel masterless. In Simpson’s work, the “belong to me aspect” of the documentary tradition—and the narrative of mastery integral to it—is far too close to the “belong to me aspect” of slavery, domestic work, and the history of sexual labor to be greeted with anything other than a fist, a turned back,and an awareness of her own “guarded condition” within visual representation.12For an excellent discussion of these guarded conditions in television, fiction,and critical theory for the African-American woman see Michele Wallace’s Invisibility Blues.

Unmoored from the traditional position of authority guaranteed by the conventions of address operative in the documentary tradition of the photograph, a tradition which functions to assure that the given to be seen belongs to the field of knowledge of the one who looks, Simpson’s photographs call for a form of reading based on fragments, serialization, and the acknowledgment that what is shown is not what one wants to see. In this loss of security, the spectator feels an inner splitting between the spectacle of pain she witnesses but cannot locate and the inner pain she cannot express. But she also feels relief to recognize the historical Real which is not displayed but is nonetheless conveyed within Simpson’s work.

In Festa’s work, a similar splitting occurs. Unfitted is an elaborate pun on the notion of women’s strength. The “labor” of the performance alludes to the labor of the delivery room—and the white sheets and red headdress are puns on the colors of the birthing process—the white light in the center of pain and the red blood which tears open that light.13Festa actually began the Untitled performance wearing a white rabbit headdress,which is lighter and cooler than the red; she has on other occasions worn the redone and the themes of “red” and “white” are constant preoccupations of herwork. The heat during Untitled (in the nineties) was intense enough that shewas eventually persuaded to abandon the white headdress. The projected feet wryly raise the issue of the fetishized female body— the part (erotically) substituted for the w/hole—which the performance as a whole—seeks to confront. As one tries to find a way to read this suspended and yet completely controlled and confined body, images of other women tied up flood one’s eyes. Images as absurdly comic as the damsel Nell tied to the railroad ties waiting for Dudley Doright to beat the clock and save her, and as harrowing as the traditional burning of martyrs and witches, coexist with more common images of women tied to white hospital beds in the name of “curing hysteria,” force-feeding anorexics, or whatever medical malaise by which women have been painfully dominated and by which we continue to be perversely enthralled.

The austere minimalism of this piece (complete silence, one performer, no overt action), actually incites the spectator toward list-making of this type. The lists become dizzyingly similar until one finds it almost impossible to distinguish between Nell screaming on the railroad tracks and the hysteric screaming in the hospital. The riddle is as much about figuring out how they became separated as about how Festa puts them back together.

The anorexic who is obsessed by the image of a slender self, Nell who is the epitome of cross-cutting neck-wrenching cartoon drama, the martyr and witch whose public hanging/burning is dramatized as a lesson in moral certitude—either on the part of the victim-martyr or on the part of the witch’s executioner—are each defined in terms of what they are not—healthy, heroic, or legitimately powerful. That these terms are themselves slippery, radically subjective, and historically malleable emphasizes the importance of the maintenance of a fluid and relative perceptual power. These images re-enact the subjective and inventive perception which defines The Fall more profoundly than the fertile ground which the story usually insists is the significant loss. The image of the woman is without property; she is groundless. But since she is “not all,” that is not all there is to the story. Emphasizing the importance of perceptual transformation which accompanied the loss of prime real estate in the Garden, Festa’s work implicitly underlines this clause—“The eyes of both of them were opened” (Genesis 3, 7)—as the most compelling consequence detailed in this narrative of origin.

The belief that perception can be made endlessly new is one of the fundamental drives of all visual arts. But in most theatre, the opposition between watching and doing is broken down; the distinction is often made to seem ethically immaterial.14This is one of the reasons “shock” is such a limited aesthetic for theatre. Itis hard to be shocked by one’s own behavior/desire, although easy to be bysomeone else’s. Festa, whose eyes are covered with tape throughout the performance, questions the traditional complicity of this visual exchange. Her eyes are completely averted and the more one tries to “see” her the more one realizes that “seeing her” requires that one be seen. In all of these images there is a peculiar sense in which their drama hinges absolutely on the sense of seeing oneself and of being seen as Other. Unlike Rainer’s film The Man Who Envied Women in which the female protagonist cannot be seen, here the female protagonist cannot see. In the absence of that customary visual exchange, the spectator can see only her own desire to be seen. The satisfaction of desire in this spectacle is thwarted perpetually because Festa is so busy conferring with some region of her own embryology that she cannot participate in her half of the exchange; the spectator has to play both parts—she has to become the spectator of her own performance because Festa will not fulfill the invitation her performance issues. In this sense, Festa’s work operates on the other side of the same continuum as Rainer’s. Whereas in the film Trisha becomes a kind of spectator, here the spectator becomes a kind of performer.

But while Festa successfully eliminates the ethical complicity between watching and doing associated with most theatre, she does not create an ethically neutral performance. Festa’s body is displayed in a completely private (in the sense of enclosed) manner in a public spectacle. She becomes a kind of sacrificial object completely vulnerable to the spectator’s gaze. As I watch Festa’s exhaustion and pain, I feel cannibalistic, awful, guilty, “sick.” But after a while another more complicated response emerges. There is something almost obscenely arrogant in Festa’s invitation to this display. It is manifest in the “imitative” aspect of her allusions to Christ’s resurrection and his bloody feet, and latently present in the endurance she demands of both her spectator and herself. This arrogance, which she freely acknowledges and makes blatantly obvious, in some senses, “cancels” my cannibalism. While all this addition and subtraction is going on in my accountanteyes, I begin to realize that this too is superficial. The performance resides somewhere else—somewhere in the reckoning itself and not at all in the sums and differences of our difficult relationship to it. But this thought does not allow me to completely or easily inhabit a land of equality or democracy, although I believe that is part of what is intended. I feel instead the terribly oppressive physical, psychic, and visual cost of this exchange. If Festa’s work can be seen as a hypothesis about the possibility of human communication, it is an uncompromising one. There is no meeting-place here in which one can escape the imposing shadow of those (bloody) feet: if History is figured in the tape loop as a repetitious birth cycle, the Future is figured as an unrelenting cycle of death. Where e. e. cummings writes: “we can never be born enough,” Festa counters: “we can never die sufficiently enough.” This sense of the ubiquitousness of death and dying is not completely oppressive, however (although at times it comes close to that)—because the performance also insists on the possibility of resurrection. By making death multiple and repetitious, Festa also makes it less absolute—and implicitly, less sacred—not so much the exclusive province of the gods.

My hesitation about this aspect of Festa’s work stems not from the latent romance of death (that’s common enough), but rather from her apparent belief (or perhaps “faith” is a better word) that this suspension/ surrender of her own ego can be accomplished in a performance. It is this belief/faith which makes Festa’s work so extravagantly literal. Festa’s piece is contingent upon the possibility of creating a narrative which reverses the narrative direction of The Fall; beginning with the post-lapsarian second-order of Representation, Festa’s Untitled attempts to give birth—through an intense process of physical and mental labor— to a direct and unmediated Presentation-of-Presence. That this Presence is registered through the body of a woman in pain is the one concession Festa makes to the pervasiveness (and the persuasiveness) of postlapsarian perception and Being. Enormously and stunningly ambitious, Festa’s performances leave both the spectator and the performer so exhausted that one cannot help but wonder if the pleasure of presence and plenitude is worth having if this is the only way to achieve it.

In the spectacle of endurance, discipline, and semi-madness that this work evokes, an inversion of the characteristic paradigms of performative exchange occurs. In the spectacle of fatigue, endurance, and depletion, Festa asks the spectator to undergo first a parallel movement and then an opposite one. The spectator’s second “performance” is a movement of accretion, excess, and the recognition of the plenitude of one’s physical freedom in contrast to the confinement and pain of the performer’s displayed body.

IIIIn The History of Sexuality Foucault argues that “the agency of domination does not reside in the one who speaks (for it is he who is constrained), but in the one who listens and says nothing; not in the one who knows and answers, but in the one who questions and is not supposed to know” (Sexuality: 64). He is describing the power-knowledge fulcrum which sustains the Roman Catholic confessional, but as with most of Foucault’s work, it resonates in other areas as well.

As a description of the power relationships operative in many forms of performance Foucault’s observation suggests the degree to which the silent spectator dominates and controls the exchange. (As Dustin Hoffman made so clear in Tootsie, the performer is always in the female position in relation to power.) Women and performers, more often than not, are “scripted” to “sell” or “confess” something to someone who is in the position to buy or forgive.

Much Western theatre evokes desire based upon and stimulated by the inequality between performer and spectator—and by the (potential) domination of the silent spectator. That this model of desire is apparently so compatible with (traditional accounts of) “male” desire is no accident.15In fact it may account for the intense male homoeroticism of so much of theatrical history. But more centrally this account of desire between speaker/ performer and listener/spectator reveals how dependent these positions are upon visibility and a coherent point of view. A visible and easily located point of view provides the spectator with a stable point upon which to turn on the machinery of projection, identification, and (inevitable) objectification. Performers and their critics must begin to redesign this stable set of assumptions about the positions of the theatrical exchange.

The question raised by Festa’s work is the extent to which interest in visual or psychic aversion signals an interest in refusing to participate in a representational economy at all. By virtue of having spectators she accepts at least the initial dualism necessary to all exchange. But Festa’s performances are so profoundly “solo” pieces that this work is obviously not “a solution” to the problem of women’s representation.

Festa addresses the female spectator; her work does not speak about men, but rather about the loss and grief attendant upon the recognition of the chasm between presence and re-presentation. By taking the notion that women are not visible within the dominant narratives of history and the contemporary customs of performance literally, Festa prompts new considerations about the central “absence” integral to the representation of women in patriarchy. Part of the function of women’s absence is to perpetuate and maintain the presence of male desire as desire—as unsatisfied quest. Since the female body and the female character cannot be “staged” or “seen” within representational mediums without challenging the hegemony of male desire, it can be effective politically and aesthetically to deny representing the female body (imagistically, psychically). The belief, the leap of faith, is that this denial will bring about a new form of representation itself (I’m thinking only half jokingly of the sex strike in Lysistrata: no sex till the war ends). Festa’s performance work underlines the suspension of the female body between the polarities of presence and absence, and insists that “the woman” can exist only between these categories of analysis.

Redesigning the relationship between self and other, subject and object, sound and image, man and woman, spectator and performer, is enormously difficult. More difficult still is withdrawing from representation altogether. I am not advocating that kind of retreat or hoping for that kind of silence (since that is the position assigned to women in language with such ease). The task, in other words, is to make counterfeit the currency of our representational economy—not by refusing to participate in it at all, but rather by making work in which the costs of women’s perpetual aversion are clearly measured. Such forms of accounting might begin to interfere with the structure of hommosexual desire which informs most forms of representation.

IVBehind the fact of hommo-sexual desire and representation the question of the link between representation and reproduction remains. This question can be re-posed by returning to Austin’s contention that a performative utterance cannot be reproduced or represented.

For Lacan, the inauguration of language is simultaneous with the inauguration of desire, a desire which is always painful because it cannot be satisfied. The potential mitigation of this pain is also dependent upon language; one must seek a cure from the wound of words in other words— in the words of the other, in the promise of what Stevens calls “the completely answering voice” (“The Sail of Ulysses,” in The Palm at the End: 389). But this mitigation of pain is always deferred by the promise of relief (Austin’s performative), as against relief itself, because the other’s words substitute for other words in an endless mise-en-abyme of metaphorical exchange. Thus the linguistic economy, like the financial economy, is a ledger of substitutions, in which addition and subtraction (the plus and the minus) accord value to the “right” words at the right time. One is always offering what one does not have because what one wants is what one does not have—and for Lacan, “feelings are always reciprocal,” if never “equal.”16Lacan, no citation, quoted in Felman, The Literary Speech Act:29. Exchanging what one does not have for what one desires (and therefore does not have) puts us in the realm of the negative and the possibility of what Felman calls “radical negativity” (The Literary Speech Act: 143).

While feminist theorists have been repeatedly cautioned about becoming stuck in what Sue-Ellen Case describes as “the negative stasis of what cannot be seen,” I think radical negativity is valuable, in part because it resists reproduction.17Sue-Ellen Case, “Introduction,” in Performing Feminisms,ed. Case: 13.For other warnings about the negativity of feminist theory see: Linda Alcoff,“Cultural Feminism versus Poststructuralism: The Identity Crisis inFeminist Theory”; Laura Kipnis, “Feminism: the Political Conscience of Post-modernism?”; in Universal Abandon?, ed. Ross; and Janet Bergstromand Mary Ann Doane, “The Female Spectator: Contexts and Directions,” Camera Obscura (20–21) May-September 1989. Felman remarks: “radical negativity is what constitutes in fact the analytic or performative dimension of thought: at once what makes it an act” (original emphases; ibid.: 143). As an act, the performance of negativity does not make a claim to truth or accuracy. Performance seeks a kind of psychic and political efficacy, which is to say, performance makes a claim about the Real-impossible. As such, the performative utterances of negativity cannot be absorbed by history because their affects/effects, like the constative utterances about stolen paintings which Sophie Calle turns into performatives by framing them in the gallery, are always changing, varied and resolutely unstatic objects. “What history cannot assimilate,” Felman argues, “is thus the implicitly analytical dimension of all radical or fecund thoughts, of all new theories: the ‘force’ of their ‘performance’ (always somewhat subversive) and their ‘residual smile’ (always somewhere selfsubversive)” (original emphases; ibid.).

The residual smile is the place of play within performance and within theory. Within play the failure to meet, the impossibility of understanding, is comic rather than tragic. The stakes are lower, as the saying goes. Within the relatively determined limits of theory, the stakes are low indeed.

Or are they?

The performance of theory, the act of moving the “as if” into the indicative “is,” like the act of moving descriptions of paintings into the frames of the stolen or lent canvases, is to replot the relation between perceiver and object, between self and other. In substituting the subject’s memory of the object for the object itself, Calle begins to redesign the order of the museum and the representational field. Institutions whose only function is to preserve and honor objects—traditional museums, archives, banks, and to some degree, universities—are intimately involved in the reproduction of the sterilizing binaries of self/other, possession/dispossession, men/women which are increasingly inadequate formulas for representation. These binaries and their institutional upholders fail to account for that which cannot appear between these tight “equations” but which nonetheless inform them.

These institutions must invent an economy not based on preservation but one which is answerable to the consequences of disappearance. The savings and loan institutions in the US have lost the customer’s belief in the promise of security. Museums whose collections include objects taken/purchased/obtained from cultures who are now asking (and expecting) their return must confront the legacy of their appropriative history in a much more nuanced and complex way than currently prevails. Finally, universities whose domain is the reproduction of knowledge must re-view the theoretical enterprise by which the object surveyed is reproduced as property with (theoretical) value.